Thursday, May 31, 2012

Structure Constitutes More Than Its Elements

Structure's Boundary Conditions—Wholeness, Transformation, Self-Regulation

Piaget began his inquiries into structuralism by first isolating what was common

to all structuralist thought. Number one on his list was the "affirmative

ideal"; that is, the ideal of intelligibility aspired after by all

structuralists. In addition to the definitions that were proffered by various

structuralists as part of the "affirmative ideal," Piaget also understood structure

to be more than the sum total of its elements.

Structuralism, according to Piaget, is also characterized by transformations, e.g., 2=1+1, the synchronic/diachronic distinction, not not A = A, and by self-regulation

processes that tend to maintain and perpetuate the continued existence of

structures. Thus, in so far as structuralism is characterized by transformations, the

laws that constitute structure must themselves be structuring. Piaget clarifies:

"Indeed, all known structures--from mathematical groups to kinship systems--are,

without exception, systems of transformation. But transformation need not be a

temporal process: 1+1 "make" 2; 3 "follows hard on" 2; clearly, the "making" and

"following" here meant are not temporal processes. On the other hand,

transformation can be a temporal process: getting married "takes time." Were it

not for the idea of transformation, structures would lose all explanatory

import, since they would collapse into static forms." [Jean Piaget,

Structuralism, 1970, p.12]

The self-regulation aspect of structuralism may be considered from a logical or mathematical point of view, i.e., the rules defining structure, (or, in the self-maintenance systems that define a healthy organism). Within the diverse range of the structuralist

movement, Piaget located the boundary conditions for structuralism in the

attributes -- wholeness, transformation, and self-regulation. However, to the

extent that structure can be formalized, Piaget believed that structure should be formalized. Because the significance of this concept, "the limits of structural formalization" is so important, I now digress to a brief discussion concerning foundational problems in mathematics, i.e., a discussion concerning "the limits of structural formalization."

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

Experience Is Structured Along Subject And Object Poles

Logic Of The Spontaneous Organization Of Activity In The Thought Of Piaget

"There seems to be little evidence that Cassirer, Mead, and Piaget ever had much

direct influence on one another. This makes all the more interesting their

convergence on a common point of view." [Don Martindale, 1981, p.339] Indeed,

whereas Cassirer found the origin and evolution of symbolic meaning to reside in

the "work" of man, Piaget, in a like manner, put the origin of structure and the

symbolic content that it generates, in the organisms capacity for action. Howard

Gardner has this to say regarding the priority of the act in Piaget's psychology:

"Piaget reached a crucial insight: the activity of an organism can be described

or treated logically, and logic itself stems from a sort of spontaneous

organization of activity. At this time he also formulated the notion that all

organisms consist of structures--i.e., of parts related within a whole--and that

all knowledge is an assimilation of a given external into the structures of the

subject." [Howard Gardner, The Quest for Mind, Piaget, Levi-Strauss, and the

Structuralist Movement, 1973, p.54]

In addition to the similarity that occurs in Cassirer's and Piaget's concepts

of "work" and "action" the thought of these two men converge in another respect

also. Both men believed that the subject and object poles of experience are not

simply "given." Rather, for Cassirer and Piaget, the subject and object poles

of experience are "products of experience.” As we have already seen, Cassirer

came to this conclusion, at least in part, based on his studies of Pre-modern

man's mythology. Piaget, on the other hand, arrived at this conclusion as a

result of his investigations into the language acquisition of young children. In

a study of early two-word utterances Piaget (1951) “was able to show how the

subject pole and object pole of a child's experience remains undissociated in

the early stages of language development." [Edited by B.Z. Presseisen, Topics in

Cognitive Development, 1978, p.7]

For Piaget, the long and active process that results in what we take to be the

knowledge of our objective and subjective experience begins in the recognition

and coordination of sensorimotor activity. By locating the source of cognitive

structure in the sensorimotor activity of babies, Piaget opened up the

possibility that structure was grounded in nature and not in mind. In his

investigations Piaget inquired into the source of this structure. He asked the

question, "Did structure lie in man, nature, or both? In an attempt to answer

this question Piaget offers us his own constructionist structuralist method.

Monday, May 28, 2012

Claude Levi-Strauss—Summation

Tapping Into The Panhuman Mainstream Of Objective Thought

For Levi-Strauss man is engaged in a society that is not just a simple

reflection of the mind's universal internal categories, man is engaged in a

society which is a determining agent in itself, a determining agent arising out

of the unconscious laws of semiological systems. The mind, according to this

view, is a thing among things, arising from the same laws that produce culture

and societal relationships. This idea becomes more clear if you consider a

famous passage from the introduction to The Raw and the Cooked, (where

Levi-Strauss... defended himself against the criticism that his interpretations

of South American myth may tell more about the interpreter's thinking than about

that of the Indians):

"For, if the final goal of anthropology is to contribute to a better knowledge

of objective thought and its mechanisms, it comes to the same thing in the end

if, in this book, the thought of South American Indians takes shape under the

action of mine, or mine under the action of theirs.

"Here Levi-Strauss assumes that it is possible to by-pass the problems of

social and cultural analysis that are central to anthropology and to tap

directly into the panhuman mainstream of objective thought." [David

Maybury-Lewis, Wilson Quarterly, 12:82-95]

Is it any wonder that critics of structuralism respond that structuralism is

not humanism because it takes away, or refuses to grant, man any status in the

world? Levi-Strauss's anthropology and philosophy cannot, in my opinion, escape

the bite of this criticism. In the psychology of Jean Piaget we encounter

another variety of structuralism which attempts to analyze the structural

origins of mind from a less fixed point of view. It is now to Piaget's

structuralism that we turn.

Society Is The Determining Agent For Levi-Strauss

But Who Fathered The First Mother?

Using the concept of binary opposition, Levi-Strauss analyzes the Greek Oedipus

myth into its constituent parts. For Levi-Strauss, the problem of the

relationship of these parts becomes resolved in the third level of semiological

analysis, i.e., the continuum of successive and related oppositions. For

instance, he tells us that, in order to analyze a myth, we should isolate and

identify its constituent units, and that we should write down these units, in

the form of sentences, on multiple small cards. These sentences should describe

a certain function as it relates to a subject at a particular time, as in the

case of "Kadmos kills the dragon" in the Oedipus myth. When we group these cards

according to common relationships we not only get the myths diachronic meaning

(a record of events as they occur in the story), we also get the myths

synchronic meaning (the "langue" side of myth-- its structure frozen in time).

By using this technique (Strauss compares this technique to reading an orchestra

score sheet the harmony part of which is read vertically while the melody is

read horizontally) the synchronic and diachronic levels of mythological meaning

come into view, thus Levi-Strauss tells us: "There-from comes a new hypothesis

which constitutes the very core of our argument: the true constituent units of a

myth are not the isolated relations but bundles of such relations and it is

only as bundles that these relations can be put to use and combined so as to

produce a meaning."[Ibid. p. 293]

In his essay on myth, Levi-Strauss, goes on to identify the bundles of

relations that define the Oedipus myth and he comes up with an interpretation of

the myth that is supposed to show how man, through his mythology, copes with the

enigmas and inconsistencies which occur in nature, e.g., birth/death, the

cultural answer to origins as opposed to biological answers, etc. To sum up,

Levi-Strauss's analysis of myth plays one group of binary opposites over and

against another group of binary opposites in the belief that, on some level,

conflicting opposites tend to neutralize one another, or, at the very least,

make myth and myth making a lively, productive and ongoing utilitarian

experience. But, after all is said and done, the question, "Who fathered the

first mother?" still persists.

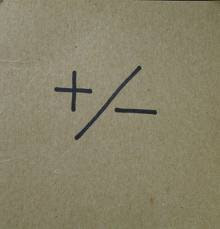

When The Brain Acquired The Ability To Make Plus/Minus Distinctions

Search For Mind Code Continues

A major influence on Levi-Strauss's anthropology came by way of Marx and Freud.

Both of these men tended to place extreme emphasis on the concealed aspect of

the motivational force behind human behavior. For Marx this motivational aspect

was a natural consequence following from the social fabric of social structure

and economic realities, while for Freud these motivational aspects were

repressed deep within the person's psychological experience of the

unconsciousness. Following the path of the thought of these men Levi-Strauss

identified gift giving as the integrative function promoting social solidarity, i.e.,

the incest taboo to be part of the hidden matrix holding together kinship

systems. But, for Levi-Strauss, the hidden agenda behind a person's motivational

consciousness is nowhere more revealing than can be found in the mythology of

any given culture.

Levi-Strauss began his investigations of myth with the publication of “The

Structural Study of Myth” (1955). He believed myth to contain the "universal

code" that if properly understood would unlock the door to the unconscious as

well as the conscious mind. For Levi-Strauss, mind represented an objective component of the brain and, like any other object, the principles underlying its constitution could be investigated and discovered. With this end as his goal, he investigated the structural nature of myth. In his book, “The Savage Mind,” he sought to disclose in his description of the "concrete logic" of Pre-modern man that "...there is no such thing as `The Primitive Mind'; or, for that matter, `Modern Mind'; there is only `Mind-As-Such.'" [Hayes and Hayes, editors, Claude Levi-Strauss: The Anthropologist As Hero, 1970, p.224]

One cannot read very far into the works of Levi-Strauss without concluding that

he believed he had found the mind's code, however subtle, variable, and

kaleidoscopically shifting it was, in the elementary logic of Pre-modern man.

According to Bottomore and Nisbet, this universal logic becomes identifiable in

the significance Levi-Strauss places in the concept of binary opposition:

"Levi-Strauss argues that man, by the very nature of his mind, views the world

with binary concepts--for example, odd and even numbers. ...(M)an's capacity to

symbolize with his fellows requires that in the course of evolution the brain

acquired the ability to make "plus/minus distinctions for treating the binary

pairs thus formed as related couples, and for manipulating these relations as in

a matrix algebra." [Tom Bottomore and Robert Nisbet, A History of Sociological

Analysis, 1979, p.584]

It was precisely in the significance Levi-Strauss attributed to binary

opposition that lead him to believe "the mythical value of myth remains

preserved, even through the worst translation." [W. A. Lessa and E.Z. Vogt,

Claude Levi-Strauss, The Structural Study Of Myth, p. 292] Using the framework

of binary opposition, Levi-Strauss has given us a description of how to

structurally analyze myth. Accordingly, myths are more susceptible to a

semiological analysis then were kinship systems and he wastes no time in making

that analogy. Acknowledging the Saussurean principle of the arbitrary character

of linguistic signs, he says:

"In order to preserve its (Myth) specificity we should thus put ourselves in a

position to show that it is both the same thing as language, and also something

different from it. Here, too, the past experience of linguists may help us. For

language itself can be analyzed into things which are at the same time similar

and different. This is precisely what is expressed in Saussure's distinction

between langue and parole...If those two levels already exist in language, then

a third one can conceivably be isolated." [Ibid. p. 291]

Sunday, May 27, 2012

Claude Levi-Strauss—Code Searching

The Kinship System As A Form Of Language

Although one could argue that Levi-Strauss is as Kantian in outlook as is

Chomsky, it quickly becomes apparent after reading some of Levi-Strauss's

anthropology that there will be no attempt on his part to populate his mansions

with real, freedom loving people. Whereas, as I have already pointed out, Kant

makes an attempt to personalize his transcendental subject, Paul Ricoeur tells

us "Levi-Strauss's philosophy is a Kantianism without a transcendental subject."

[Philip Pettit, p. 78] Levi-Strauss's zealous attempt to capture the categories

of mind in his structural analysis of myth, kinship, and totemism turns the

subject into an object via his structural analysis.

Levi-Strauss's 1949 study of kinship systems came at the beginning of his

career, before he had fully developed his structuralist method. But, in his

approach to kinship, his method was already apparent. Levi-Strauss

brought to this study a collectivist, functionalist perspective. He was

following the line of study already documented in the works of Durkheim and

Mauss. In his emphasis on using women as objects for gift giving, he was simply

extending Mauss's thesis that gift giving promotes social solidarity within

one's own culture as well as promoting a cross culture solidarity when gifts are

cross culturally exchanged. Like Mauss, Levi-Strauss believed that these

reciprocal relationships were established for integrative rather than for

economic purposes.

Kinship relationships are varied and perplexing. All societies have to have

social arrangements which allow men and women to get together for the purpose of

having children. For Levi-Strauss the incest taboo became the distinguishing

characteristic which sets man apart from other animals. This rule, that one had

to marry outside of the family, became the first principle in his kinship

system. The second and more controversial principle could be found in his

explanation concerning who gets to marry who.

"In early human societies," Lewis informs us, "kinship was too important a matter to be left to chance or to individual whim. Systems of regular intermarriage among groups were therefore set up, and Levi-Strauss demonstrated ingeniously how they could have resulted from the idea of marrying out, but not too far out, i.e., marriage between

certain kinds of first cousins." [David Maybury-Lewis, Claude Levi-Strauss and

the Search for Structure, Wilson Quarterly, 12:82-95] This cross culture

marriage and exchange of cousins (usually on the maternal side but not always)

became the key, according to Levi-Strauss, that unlocked the perplexing nature

of kinship systems.

Another suggestive and more structuralist feature of Levi-Strauss's analysis of

kinship systems is found in his claim that marriage regulations and kinship

systems are a kind of language. He says:

(Marriage regulations and kinship systems are)… “a set of processes permitting

the establishment, between individual and groups, of a certain kind of

communication. That the mediating factor, in this case, should be the women of

the group, who are circulated between clans, lineages, or families, in place of

the words of the group, which are circulated between individuals, does not at

all change the fact that the essential aspect of the phenomenon is identical in

both cases." [Philip Pettit, p.70]

Understanding kinship systems in this way moves us, once again, in search of

that “illusive code," fixed in time and waiting to be discovered, that

ultimately, Levi-Strauss believes to be at the core of his investigations. In

his structural analysis of myth this quest continues.

Friday, May 25, 2012

Free And Spontaneous Acts Of The Human Spirit--Chomsky

Free And Spontaneous Acts Of Inquiry Through Self-Expression

Chomsky's concept of "innate qualities of mind" must itself be understood as a

form of the creative aspect of mind for, in his analysis of deep structure and

surface structure, he describes a system of rules for generating sentences and

the sorts of words that may replace any given word in a sentence, in the context

of a creative process. He says: (Human language)..."is free to serve as an

instrument of free thought and self-expression. The limitless possibilities of

expression constrained only by rules of concept formation and sentence

formation, these being in part particular and idiosyncratic but in part

universal, a common human endowment."[Ibid. p. 29]

For Chomsky, the deep structure that expresses the meaning of the sentence is

common to all languages. It is the transformation rules that rearrange, replace,

or delete items of a sentence that differ from one language to the next. In

conjunction with language's deep and surface structures these transformation

rules come together in the form of the "organic" nature of language in which,

according to Chomsky, all the parts are interconnected and the role of each

element is determined by the generative processes that constitute language's

underlying form. Language, from Chomsky's point of view, even though it is

conditioned upon maturational processes, and interaction with the social and

physical environment, is understood to be free from stimulus control as it

permits the spontaneous activity of inquiry and self-expression. Chomsky, in

this sense, if not totally successful, at least attempts to secure in his

structuralist interpretation of language, a place for the free and spontaneous

acts of the human spirit.

Chomsky-Deep Structure Is Common To All Sentence Meaning

The Saussure Chomsky Difference

Whereas Saussure dealt with language in terms of a holistic system of

differentiation, Chomsky extends this system into the realm of transformational

or generative grammar. Saussure's structuralism did not build bridges between

itself and Kantian philosophy. It might even be argued, in fact, that Saussure

tried to burn a few of these bridges. Except for his use of certain essential

Kantian categories, e.g., identity (memory), plurality, differentiation etc.,

Saussure's structuralism restricts itself to organizing and orientating the

methodological study of language. Chomsky, on the other hand, developed a

differentiating, holistic theory of language that allows for novelty and

creativity. Saussure's langue and parole, in Chomsky's linguistics, became

language competence and performance. With the performance attribute of language,

Chomsky took a syntagmatic approach to language which essentially means that

Chomsky added to Saussure's theory a recursive body of rules for the purpose of

generating syntax or sentences in the performance of speech. This generative

syntax became one component of the two-component aspect of Chomsky's linguistic

theory.

Chomsky believed language to be a product of both a deep and surface structure

of mind. In this respect, he split language syntax into two levels, one to

describe the deep structure of language and one to show how this deep structure

transforms into surface structure.

[Footnote. Chomsky illustrates: To take a simple case, consider the sentences

"John appealed to Bill to like himself" and "John appeared to Bill to like

himself." The two sentences are virtually identical in surface form, but

obviously quite different in interpretation. Thus when I say "John appealed to

Bill to like himself," I mean that Bill is to like himself; but when I say "John

appeared to Bill to like himself," it is John who likes himself. It is only at

what I would call the level of "deep structure" that the semantically

significant grammatical relations are directly expressed in this case. Noam

Chomsky, Problems of Knowledge and Freedom, 1971, p.24]

In this regard Chomsky is giving language analysis a more Kantian perspective.

Chomsky was not shy about his belief in innate structures of the mind. Kant's

influence becomes apparent when he says:

"There are, then, certain language universals that set limits to the variety of

human language. The study of the universal conditions that prescribe the form of

any human language is "grammaire generale." Such universal conditions are not

learned; rather, they provide the organizing principles that make language

learning possible, that must exist if data is to lead to knowledge. By

attributing such principles to the mind, as an innate property, it becomes

possible to account for the quite obvious fact that the speaker of a language

knows a great deal that he has not learned." [Noam Chomsky, Cartesian

Linguistics, 1966, p.59]

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Search For The Hidden Code At The Heart Of Language, Myth, Literature, History

The Diachronic Axis Of Language

The concept of "irreducibility" is a universal concern of all structuralist

thought. In Kant we witnessed his desire to identify the defining "universals"

of all human experience. In Saussure this desire becomes fulfilled in his

systematic and holistic interpretation of language. Shortly, we will be talking

about how Levi-Strauss, Piaget, and Foucault express this same idea. The

credibility of structuralism rests, I believe, on making the synchronic aspect

of nature intelligible and accountable to some form of empirical verification.

Saussure's synchronic nature of language, at least in the form of linguistic

theory, moves us in that direction. Sensitive to this issue, Saussure believed

he was removing the mystery of language and placing it in the material world

with his concept of language's synchronic aspect. And, indeed, this idea that

language can be understood synchronically, frozen in time, has inspired many

structural investigations into the "hidden code" that the proponents of

structuralism believe lies at the heart of language, myths, literature and history.

At the very least, after Saussure, there arose a new skepticism for any

investigation of language that had as its goal the disclosure of the "essence

of language.”

In addition to its synchronic component, language may also be characterized, in

the terminology of Saussure, along its diachronic axis. Language evolves as the

expression of a collectivity moving through time. Language is not invulnerable

to societal or cultural pressures. The institution of language, over time,

becomes violated by dialects and slang. Language changes, but it does so

according to its own inertia. According to Michael Lane, this evolution takes

place as a result of societal pressures and influences. Lane says:

"This is apparent from the way in which language evolves. Nothing could be more

complex. As it is a product of both the social force and time, no one can change

anything in it, and, on the other hand, the arbitrariness of its signs

theoretically entails the freedom of establishing just any relationship between

phonetic substance and ideas. The result is that each of the two elements united

in the sign maintains its own life to a degree unknown elsewhere, and that

language changes, or rather evolves, under the influence of all the forces which

can affect either sounds or meanings. The evolution is inevitable; there is no

example of a single language that resists it. After a certain period of time,

some obvious shifts can always be recorded." [Michael Lane, Introduction to

Structuralism, 1970, p.51]

Language, at any given moment in time, may be investigated along its synchronic

or diachronic axis. Structuralism, for the most part, prefers to study language

in its synchronic aspect. It is for precisely this reason that structuralism

opens itself up to attack by those schools of thought which deny the possibility

of studying anything whatsoever independent of its social context, e.g., Marxism.

In general, structuralism, and Saussure's structural linguistics in particular,

have also been criticized for its disregard for human creativity. Noam Chomsky,

a leading advocate of structural linguistics in today's academic environment,

has responded to the latter criticism with his discovery and development of

transformational grammar.

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Fixed Nature Of Wholes In Language—The Synchronic Axis Of Language

Language Depends On The Word For Its Field Of Signification-The Word Depends On

Language For Its Meaning-Reciprocal Movement

Once Saussure had delineated the structure of the word, he also delineated the

structure of language. For Saussure, the sign relates to language in the same

way as the signifier relates to the signified. The word, as opposed to being a name for an object, is a differentiation in the set of linguistic units that, when taken as a whole, constitute a language. A word acquires its meaning, according to Saussure, in the way it differentiates itself from the whole, the whole being the collective expression of an entire language. We find here the same double movement constituting the meaning of the sign as it relates to language, as we did in the word relationship of signifier to signified. Here the word becomes dependent on language for its meaning and language becomes dependent on the word for its "field of

signification." Thus the arbitrary character of the sign is what

permits order and meaning to arise in the world. John Sturrock, in his book

“Structuralism and Since,” underscores this distinction when he says:

"The extremely important consequence which Saussure draws from this twofold

arbitrariness is that language is a system not of fixed, unalterable essences

but of labile forms. It is a system of relations between its constituent units,

and those units are themselves constituted by the differences that mark them off

from other, related units. They cannot be said to have any existence within

themselves, they are dependent for their identity on their fellows. It is the

place which a particular unit, be it phonetic or semantic, occupies in the

linguistic system which alone determines its value. Those values shift because

there is nothing to hold them steady; the system is fundamentally arbitrary in

respect of nature and what is arbitrary may be changed." [John Sturrock,

Structuralism From Levi-Strauss to Derrida, 1979, p.10]

Saussure, using the above characterization of language, distinguishes between

langue and parole. Parole becomes the particular acts of linguistic expression

in speech while langue becomes the component aspect of language

that generates meaning through the internal play of differences. In

this respect, language forms a system of contrasts, distinctions, and oppositions

that come together in the form of pure values which, as Sturrock points out, are

solely determined by how they differ from each other as they are produced in the

system of language. Thus, language becomes a theoretical system

operating according to linguistic rules where in speakers of language, in order to

communicate, must obey these rules. It then becomes the job of linguistics

to discover the mechanisms which make language possible.

Language, in addition to being inherited, forms, according to Saussure, a corpus of

linguistic rules arising out of ahistorical conditions that allow a person to

understand and be understood. To the extent that language succeeds in this

endeavor, it is collectively determined and not susceptible to arbitrary change.

Saussure calls this aspect of language the synchronic nature of language

and it is in this synchronic nature of language where we encounter for the first

time the idea of the "fixed nature of wholes."

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

Reciprocal Movement Is What Saussure Identifies As Word

Structure Of Language

With his analysis of language, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure

contributed greatly to the modern structuralist school of thought. Saussure

instituted into language analysis the working concept of wholeness. Prior to

Saussure, language was studied as an independent phenomena arising out of the

individual circumstances of various cultural groups. Using wholeness as a

working concept was a new idea for language theory but it was not a new idea for

the already well established tradition of organic sociology as it was expressed

in the works of Comte and Durkheim. This organic connection became evident in

what Saussure took to be the linguistic principles at work in all languages. The

purpose of language study was in fact to reveal these principles.

Saussure argued that language was a collective, orderly, and coherent

phenomenon. Language, therefore, could be studied as if it were a social system

that was susceptible to understanding and explanation as a whole. Saussure

thought of individual linguistic units as a patterned wholeness. Words, he

argued, were devoid of content when studied in isolation. Their meaningful

content arose only when they were studied in relation to one another. He based

his conception of the linguistic unit on the assumption that where there was

meaning - in a word or sentence - there would also be structure. This idea was

in conflict with the nominalist view of language that took words to be mere

names of things. For instance:

"Some people regard language, when reduced to its elements, as a naming-process

only - a list of words, each corresponding to the thing that it names. This

conception is open to criticism at several points. It assumes that ready-made

ideas exist before words; it does not tell us whether a name is vocal or

psychological in nature (arbor, for instance, can be considered from either

viewpoint); finally, it lets us assume that the linking of a name and a thing is

a very simple operation - an assumption that is anything but true. But this

rather naive approach can bring us near the truth by showing us that the

linguistic unit is a double entity, one formed by the associating of two terms."

[Michael Lane, Introduction to Structuralism, 1970, p.43]

Saussure goes on to explain how this "double entity" must be conceived. The

word, according to Saussure, unites a concept and a sound-image and not a thing

and a name. In this sense, the sound-aspect of a word becomes inseparable from

the meaning content of the word and the reverse also holds true. This double

movement, sound acquiring conceptual meaning as conceptual meaning becomes

differentiated by sound, is what Saussure identifies as the "structure" of the

word. Saussure, in the following diagrams (unfortunately, my computer only produces words) illustrates this idea.

In the diagram below (missing diagram but the idea is still there) imagine three circles, one around each of the joined identifiers. Then imagine an up and down arrow on each side of each circle—that's six arrows, three pointing up, three down-- and you will have a

mental image of Saussure's diagram.

Concept "tree" picture of tree

Sound-image arbor, connecting arrow

[Ferdinand De Saussure, Course In General Linguistics, Translated by Wade

Baskin, 1959, p. 66-67.]

In these diagrams we see a representation of the working concept of wholeness as

it becomes operationally defined in the linguistic structure of the word. Here

the two elements of sound and word become intimately united, as each refers to

the other. Saussure, by calling the sound-image of a word the signifier,

differentiates the meaning of the word into its two components, the signifier

and signified. Together, the signifier and the signified combine to form the

sign, i.e., the whole as differentiated from its opposing elements.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)