Saturday, May 19, 2012

Structuralism And Immanuel Kant's Philosophy

"Whatever we call reality, it is revealed to us only through the active

construction in which we participate." (Ilya Prigogine, Order Out Of Chaos)

Structuralism emerges from the elementaristic side of the holism/elementarism

debate as an extension of the neo-Kantian position. Form, within this tradition,

takes precedence over content, but in so far as structure itself is a holistic

concept, the actual locus of structuralism in relation to the holism/

elementarism debate is somewhat ambiguous. I believe that within this ambiguity

will be found a resolution to the holism/elementarism debate. In order to bring

this debate to a close, however, we must first look at the various

structural models that have been described in linguistics (Saussure and

Chomsky,) anthropology (Levi-Strauss,) psychology (Piaget,) and philosophy

(Foucault.) My description of these various forms of structuralism will

concentrate in the areas that have a direct bearing on bringing this debate to a

satisfactory conclusion. With that end in mind, I would like to begin by taking

a peak at the philosophy of Immanuel Kant.

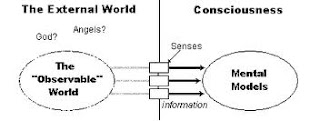

Kant, in his attempt to synthesize the rationalist thought of Descartes and

Leibnitz with the empirical thought of Locke, Berkeley, and Hume, understood

sense experience to be manipulated within the inherent structure of mental

categories. In his analysis of this structure he concluded that there is more

than one kind of knowing (Critique of Pure Reason, 1781, Practical Reason,

1788, and Judgment, 1790) but the major importance of Kant's analysis is found

in his understanding of the logical consistency and necessity of both sensed

space and time and mathematical space and time. This aspect of Kant's

philosophy, although it represented a major success for Kant, in retrospect, is

not so well received.

Just as Locke was driven to his theory of ideas by the consequences of Newton's

deterministic universe, Kant had to face a similar determinism. It was not with

atoms and forces which his determinism had to contend, rather, it was with the

determined nature of knowledge itself. Kant's transcendental ego, when pursued

to its logical conclusion, did not allow for individual freedom. He accounted

for man as knower of the universe, but he did not account for man as a free

moral agent within the universe. Kant used the presuppositional method to solve

this problem: "It is impossible to conceive anything at all in the world, or

even out of it, which can be taken as good without qualification, except a good

will." [Immanual Kant, The Moral Law, 1948, p.59]

In other words, he presupposes free will to allow for moral action i.e. Kant's

practical ego. This is a key concept because upon reading Kant the German

champion of freedom, Fichte, was able to show that it was not the categories of

understanding which allowed a person to know the universe, it was the person's

own individual will that will's knowledge of the universe through the

categories.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment