Sunday, May 20, 2012

Kant’s Categories—The Consequences

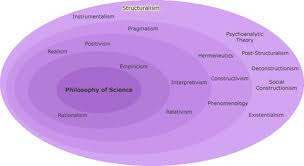

Structuralism And Kant's Philosophy Continued

The claim that one will’s, via Kant’s categories, knowledge of the universe

is more than an arbitrary assessment by Fichte on Kant's presupposed ego.

The science of Einstein, Bohr, Schrodinger and Heisenberg has

demonstrated the error in Kant's constitutive and hence necessary relationship

between the categories of understanding and reality. Thus, science has taught us

that mental categories, if indeed there are such things, are only interpretive

for the measurable observable events that we identify with reality. Within the

context of the scientific method, these events are hypothetically postulated and

aposteriorily (to use Kant's terminology) verified. Consequently, it is not the

facts that imply the theory; rather, it is the theory that implies the facts.

The breakdown of the necessary relationship between Kant's categories and

sensed experience does not invalidate Kant's distinction of sensed space and

time and mathematical space and time. Kant's philosophy, not withstanding its

assumption of necessity, is still a major force in the world today.1

It is unfortunate, however, that Fichte's identification of the will with Kant's

practical ego helped to supplement the deterministic portions of Hegel's

idealism and in no small way contributed to the totalitarian ideologies of Nazi

Germany and the U.S.S.R. In a nutshell, an ego free from the constraints of

reason, motivated purely through the expression of the will, identifies the “is

of society” with the “ought for society.” This, in turn, became the determinism by

which Hegel's "world spirit" and Marx's "dialectical materialism" swallowed up

the individual. What began in Kant as an attempt to restore and secure the

notion of a person's free will, ended up contributing to in the brutal

consequences of fascist and communist dictatorships. Here we once again see the

irony of the political animal called man. But, moving in another direction,

that is, remaining under the umbrella of Kant's transcendental ego, the more

modern movement of structuralism has come to the fore.

[1. In his ontological structuralism, W.V. Quine, a person of major significance

in the defining aspects of today's philosophy of science, establishes a Kantian

position when he takes structure (mathematical form) and events of confirmation

to be the ultimate ground for knowledge. Quine informs us that the structural

aspect (the categorical aspect) of this knowledge as it relates to verification

is, in addition to being Kantian, is also uncertain. He says, "Science ventures

its tentative answers in man-made concepts, perforce, couched in man-made

language, but we can ask no better. The very notion of object, or of one and

many, is indeed as parochially human as the parts of speech; to ask what reality

is really like, however, apart from human categories, is self-stultifying.

.....We saw that reference (structure) could be wildly interpreted without

violence to evidence. We see now that that is just part of a wider picture.

Presumably yet more extravagant departures, resistant even to

sentence-by-sentence interpretation into our own science, could conform equally

well to all possible observations." W.V. Quine, The Journal Of Philosophy,

Volume LXXXIX, NO. 1, January l992]

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment