Monday, October 31, 2011

All-Inclusive Interconnectivity

The Brahman Experience-Seat Of Freedom Essay Concluded

Distinctions Of Inside/Outside, Whole/Part, Cease To Be Meaningful

Winter ’80

Nishida went looking for "pure experience" and found it. In a pure

awakened state there is no distinction between transcendence,

immanence, and freedom. The "absolute free will," for Nishida, is at

the center of the creative world and lives through the "pulse of

creative nothingness." He used his own logic to characterize this

claim. To be fair, Nishida did not think of this logic in an

analytical sense, it was more a logic of existence. He called this

logic basho, and for me at least, this basho seems to be describing

three different levels of interconnectivity—the interconnectivity of

three different pulses of freedom.

Freedom is not a manifestation of being, it is the other way around;

out of creative nothingness arises the manifestation of being.

According to Nishida, everything that is, is within the

interconnectivity of the basho, and is at bottom, the basho of

"absolute nothingness." In all bashos a dual purpose is at work. As

the ground of everything, the logic of basho, works to support and

restrict all beings. Absolute nothingness becomes the heart and soul

of all beings, but tied to this basho is an invisible basho, the basho

of relative nothingness. "It," says Nishida, "exists only in relation

to the basho of being. It is the idea that nothingness is understood

in terms of its opposite: the notion of being." Interconnected with

all bashos-- relative nothingness, being, and absolute nothingness—is

the pulsing, creative nothingness that emerges from and returns to the

basho of absolute nothingness. I'm trying to understand this. I'm not

there yet. Here is a description of Nishida's basho as stated by Masaaki:

Nishida defines basho as "a predicate of predicates," a truly

universal, transcendent "place" in which subject and predicate are

mutually inclusive. Only the basho of "absolute nothingness" is truly

transcendent and truly universal. It is the place where the authentic

self turns around and becomes the "self without self." That means that

the "self as the basho" can reflect objects just as they are by truly

emptying itself, and can see things "by becoming things." Thus the

self as basho identifies itself with all beings in the absolute

contradictory mode of the world.

In this vision, “we get a feel" for how to resolve the paradox—the

paradox of how something--pure experience--can be both the source and

ground of being while at the same time been absolutely transcendent.

The being and the beyond distinctions that are present in the Hindu

and Buddhist distinctions of the Brahman/atman, self/not-self, are

dissolved in Nishida's basho. "When self-consciousness is completely

extinguished in the basho" says Nishida, "then the newborn `self as

the basho,' embodying the `unifying force' of absolute nothingness

from within, can fully exert its intrinsic nature as instrument to

become a creative force in the world." In the all-inclusive

interconnectivity of Nishida's basho, distinctions like

inside/outside, whole/part, cease to be meaningful.

It seems to me at least, according to what I am trying to understand

form the above, when everything is seen in full relief "just as it

is," in its suchness, there is an awakening. When all beings are seen

reflected in the absolute creative nothingness of the basho, there is

an awakening. In the experience of the absolute interpenetration of

nothingness with all the particular existents in the universe, there

is an awakening to the "eternal now." There, the distinctions

Brahman/atman, self/not-self, have no place. There, the newborn "self

as the basho," "self as absolute nothingness,'' wakes to perfect

freedom, perfect wisdom and perfect bliss. The fact that language will

not (can not) permit a description of "enlightened being," hasn't made

the paradox any less paradoxical. It's still there, with or without

language. I admire Nishida because of his struggles to get beyond that

paradox. However, I suspect that enlightenment—pure experience—is

necessary before "empty" and "full" can become one, before nirvana and

moksha can become one!

[Essay postscript: I was struggling when I wrote the above, but, intuitively,

I knew there was more to be discovered. I do not remember the date, but I will be posting (describing)—God willing, that experience as my journal unfolds. Here’s the crux of what I discovered:

The first structural liberation occurs between ~~p and ~pp, but the second structural liberation (the one that produces human consciousness) occurs only after a sufficient amount of diachronic evolution has transpired, i.e., a complexity sufficient to allow ~pp to reboot into the more liberated structure of p~p~pp, thus creating time of mind of consciousness, i.e., self-consciousness. The goal of all the above described spiritual disciplines—God by any other name, becomes manifest in the p~p~pp liberation of the “affirmative ideal” —the same “affirmative ideal” that liberated the source of meaningful symbol creation, which, in turn, opened the door to the creation of language, myth, religion, art, theoretical knowledge, and the rest of the civilizing processes that we call civilization.]

The Brahman Experience-Seat Of Freedom

The Difference Lies In Getting There Continues

Winter ’80 pic 3bhag, tat you, w48

The Upanishads teach that liberation will not be found "in outward

movement into the world." It is the inward journey into the self that

permits liberation. According to the teachings of the Upanishads, it

is the longing for meaning and purpose, plus a desire to end human

restlessness and suffering that leads a person down the path toward enlightenment.

The Bhagavad-Gita, gives us another approach to liberation. "He who

knows Atman overcomes sorrow," and here, overcoming sorrow means

practicing yoga. The Gita tells us that the final liberation, the

state where the self-imposed boundaries of individuality are

transcended, is the goal of yoga. In the Upanishad's the yogi is

called away from society, but in the Gita, in order to progress

spiritually, the aspirant is called to duty, in honor of society. The

practices of Karma Yoga and/or Bhakti Yoga (the yoga of duty and love,

respectively), if done whole-heartedly, bring liberation. In the

Bhagavad-Gita the god, Kishna, told Arjuna, the warrior prince, that

his "jiva self," his mind-body self, was not his atman. But, if he did

his duty, if he met the Pandavas, his cousins, on the battlefield

(while remaining unattached to the "fruits" of his actions), then he

would realize his atman and win release (moksha). It was no longer

necessary, taught the Gita, to renounce the world to achieve Brahman.

It should be noted that although the Gita emphases the practice of

Karma Yoga and Bhakti Yoga, it was not critical of other forms of

yoga, e.g., Hatha, Laya, Raja, etc. In that regard, its teachings

remained consistent with the earlier Upanishadic teachings.

To the best of my knowledge, yoga was not a necessary part of the

Buddhist tradition. To attain nirvana, the practices of disciplines,

both mental and physical, were necessary, however. All dharma's led to

the eightfold path, the last of the Buddha's four noble truths. In

addition to "right knowledge," the eightfold path called for ethical

behavior and meditative disciplines. Although some would argue that

the concepts of permanence and immortality were anathemas to the

Buddha, when it came to self-realization, the rejection of illusion,

the elimination of cravings, and the avoidance of narcissistic

preoccupations, the teachings of the Buddha were quite similar to

their Upanishad counterparts. But something else of interest brings

these two traditions together, something not generally talked about.

Brahman, as the innermost essence of reality and the cause of all

diversity, is the source and ground of being, yet it stands absolutely

transcendent to being. As the vitality of the cosmos, Brahman's

dynamic self-expression is an affirmation of the Absolute manifested

in both the individual and the world. For the sage, the claim that

Brahman and atman are one is an identity claim, but, at the same time,

Brahman remains the ground of being while being transcendent to being.

How can this be? The enlightened look to the self, to others, and to

the whole universe and rejoice in Brahman—"Tat tvam asi (That art

thou)." But what is "thou?" For the most part, in both Hinduism and

Buddhism, "thou" is left as a paradox. It is not within the grasp of

language, but it is not out of reach of the self, either. The

comprehension of self (atman in Hinduism, not-self in Buddhism)

implies the comprehension of the universe as a whole—moksha in

Hinduism, nirvana in Buddhism. Knowledge and being are identical here,

and, I believe, by taking a closer look at Nishida's self-awakening

philosophy, we will better understand why this is so.

Last Word On The Disagreement With My Religion Professor

The Brahman Experience-The Seat Of Freedom Continues

The Difference Lies In Getting There

Winter ’80

Well that's about all I have to say about Uddalaka and Yajnavalkya. I

do have a few more observations, though. In lieu of our past

conversations, it seems to me that something is going on here that

needs more attention. I can't help but feel that I'm in the middle of

that "elephant thing." You know, where one blind guy holds the trunk,

and the other blind guys hold the leg and tail, respectively. They all

"see" an entirely different animal, but what they're really "seeing"

is just one big elephant.

Paraphrasing from Hopkin's descriptions of Brahman, consider the

following: The ancient sages of India perceived no chasm between

nature, humanity, and divinity. For the wise among them, all existence

was the manifestation of the universal principle, i.e., Brahman, the source

of all being, the producer and sustainer of all reality. Brahman was

the eternal that created the temporal; it was the uncountable waves of

an incomprehensible ocean.

In Nishitani's Mahayana Buddhism (and with Nishida, his teacher), something

quite similar to the "Brahman idea" is going on. For instance, just as

when Yajnavalkya found at the seat of free will, atman, Nishitani, put

absolute freedom at the core of self. For Nishitani, free will emerged

from and returned to, absolute nothingness. On the surface, absolute

nothingness and Brahman appear to be opposites—empty and full. But are

they really?

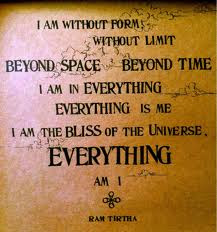

Brahman, the Absolute, is beyond all categories of time, space, and

causality. In short, it has no measure other than the fact that it

transcends all measure. Yet, if we believe the sages, Brahman can be

realized and therefore experienced. Nishitani's absolute nothingness,

like Brahman, permeates all things. If the "ripples of Brahman" vanish

back into the "timeless, spaceless, and causeless ocean of Brahman,"

then how is that any different from Nishitani's nothingness that

permeates all things? In the reciprocal case the same holds true.

Waves exist because of the ocean—the ocean being Brahman here.

All things depend on nothingness for their existence—Nishitani’s

nothingness being the source of all existence here. Where's the difference?

The sages in the Upanishads (as does the Buddha) call for the

eradication of all ignorance. We are told that when ignorance is

dispelled, "the infinitely great outside of us becomes the infinitely

great within us," which is another way of saying that our inner self,

atman, merges with our outer self, Brahman. In the Buddhist philosophy

of Nishida's self-awakening, we hear pretty much the same refrain. He

says, "When the ego awakens to its radical finitude--its nothingness,

realization occurs." In all these spiritual teachings we hear the echo

of the "outside" and "inside" becoming one. Again, "at the point of

total openness and freedom," says Nishida, "the self is no longer

separate from, but realizes its oneness with all the myriad things of

the universe." When the ego realizes the illusion of its "I," "me,"

"mine,” and stops seeing itself as an independent entity, it looks straight

through itself and sees "wholeness." Are we really talking about two different

things here? In the Chandogya Upanishad, we hear once again, --upon the

realization of atman, "the formed and the unformed, the mortal and the

immortal, the abiding and the fleeting, the being and the beyond" all

become one with Brahman. In the absolute nothingness of self, says

Nishitani, "you find the convergence of opposites—self and non self,

being and nonbeing, the personal and the impersonal, the unique and

the universal." How often do we have to hear this refrain before the

connection becomes obvious? In Brahman, we find the realization of the

unity of reality. In the "nothingness of the self," according to

Nishitani, we find the dissolution of "all contradictions of the

world, such as inside and outside, one and all, evil and good." In the

yogi's "moksha," and the Buddha's "nirvana," enlightened experience

all, where is the difference? Maybe it-- the difference-- lies in

getting there.

Disagreement With My New Religion Professor

Interchangeable Nature of Religious Concepts?

Dr. Will had a totally different teaching style. Class discussion was

not encouraged. I guess that's why things didn't jell between us. He

didn't like the way I interchanged religious concepts, either. I

finally stopped doing that, but not before, in an assigned paper on

the Upanishads, I continued to discuss what I took to be similarities

in the mystical traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism:

[The authors Uddalaka and Yajnavalkya-- From Wikipedia:

The Upanishads (Sanskrit: उपनिषद्, IAST: Upaniṣad, IPA: [upəniʂəd]) are philosophical texts considered to be an early source of Hindu religion. More than 200 are known, of which the first dozen or so, the oldest and most important, are variously referred to as the principal, main (mukhya) or old Upanishads. The Upanishads have been attributed to several authors: Yajnavalkya and Uddalaka Aruni feature prominently in the early Upanishads.]

The Brahman Experience-The Seat Of Freedom

Hindu Religion Class

Feb. 26, ’80

Uddalaka and Yajnavalkya share in the fundamental view of a timeless,

spaceless, causeless Brahman. This Brahman is the sustaining power of

the universe and is also the essence, or most essential quality found

in human beings. Brahman is beyond description, but is individualized

within a person's identifiable atman (spirit, divine self). Thus the

quest for Uddalaka and Yajnavalkya is to become conscious of their

respective atmans, however, their presentations, concerning the

aspirant's spiritual release, reflect slightly different perspectives.

Uddalaka identifies Braham as "tat tvav asi"—thou art that, thou art

that (Will's lecture, Hopkins p.44). For him, all is Brahman, and

everything else is "maya," karmic illusion. Determinateness

(appearance), for Uddalaka, is all part of the warp and woof of

Brahman. The embodied self–the atman, is only a flicker in Brahman. At

death Brahman and the embodied self merge. However, the trajectory of

that flicker (its karmic consequences) determines whether or not it

will remain in the ultimate, permanent, and undetermined state of

Brahman, or spin back into maya as another karmic-cycled life form. If

the trajectory continues back into maya then another opportunity

arises for the aspirant to work off bad karma. If the trajectory

"flickers out," then sat, chit, ananda-- perfect being, perfect

consciousness, perfect bliss becomes the experience (Will's lecture—on

liberation).

Yajnavalkya takes a slightly different approach. When he talks about

release, he emphasizes desire. For Yajnavalkya, desire fills embodied

states. Wipe out desire, and the world dissolves. Wipe out desire, and

Brahman takes its place. In order to become desireless, one must

desire an end to desire and then act on that desire, and there in lies

the problem. How can one desire something when desire itself keeps you

from attaining the desired affect? But, says Yajnavalkya, as long as

the self—atman--is desired then it is okay to desire, and knowledge,

right knowledge, is what is required in order to desire the self only.

"Knowledge of the self for Yajnavalkya," says Hopkins, "brings an end

to rebirth because it brings an end to desire for anything other than

the self. The self is the one true source of all that has value, and

thus the only true object of desire. Only ignorance of the self could

bring desire for anything else; when one knows the self, there is

nothing more that he could desire. Nothing else need be loved or held

dear, because all else is only a manifestation of the self: 'When the

self is seen, heard, reflected on and known then all this is known'

---Brihadaranyaka 4.5.6" (Hopkins, p. 42).

Through our choice of activities we create karma. For Uddalaka,

Brahman is achieved only when karmic obligations are fulfilled. For

Yajnavalkya, we desire karma until we desire "the indestructible, the

unattached, the unfettered, the insufferable—our atman" (Hopkins

p.39). In other words, for both men, certain kinds of intentional

behavior must be eliminated before one can experience Brahman, and,

typically, a teacher (guru) is sought out to help us achieve this

goal. With the help of this guru, at some point in the educational

process, right knowledge takes the place of ignorance. When this

happens, all worldly desires are left behind. "According to how a

person acts and behaves, so he becomes." (Will's law of karma lecture)

If, however, Brahman is not attained, samsaric existence continues

unabated.

In conclusion, I would like to suggest that in any teaching that calls

for spiritual progress, the most important thing to realize is first,

where you are at, and second, where do you want to go. With that

knowledge all philosophizing stops. You turn in the right direction,

or you go nowhere. It's all in that first step, however small, —in the

direction toward more freedom.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Lotus Sutra--The Mind Of The Buddha

Miss You Professor Folkart

Summer ‘80

The Lotus Sutra, at least according to some authorities,

was written at about the time of the Buddha, and, as sutras go, it was

quite large. Also, it was considered to be a highly advanced form of

Buddhist teaching. It was only taught to the Buddha’s most prized

disciples. The Buddha taught only “perfect wisdom,” that is, “right

teachings” were taught to the “right disciples” at the “right time.”

In other words, the Buddha taught only what the disciple could comprehend.

It was commonly believed that this “magical ability” to teach effectively to

all who sincerely listened, set the Buddha apart from all other

religious leaders. The Lotus Sutra was unique among sutras because the

Buddha reserved it’s teachings for only the most advanced of his disciples.

Reading the Lotus Sutra, at times, for me, was like reading a comic

book. At other times, though, it was like reading the mind of the

Buddha. It had a little bit of everything in it. It also had a lot

about “who can understand what when.” I’ll leave the heady

interpretations to the Buddhist scholars, but what I could not accept

was the claim by the monk, Nichiren, that the dharma (knowledge) that

led to enlightenment was complete in the recitation of the title of

the Lotus Sutra. The recitation of--Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, or Homage to

the Sutra of the Lotus of the Marvelous Law-- was enough to guarantee

one’s enlightenment. According to the practitioners of Nichiren

Shoshu, chanting nam myoho renge kyo was, in the age of Mappo, the

only “ticket available for enlightenment” because the Dharma of Decline had tainted all

other Buddhist teachings. For the disciples of Nichiren Shoshu, all other

Buddhist dharma was obsolete, so chant, chant, chant,--until the cows come home.

This nasty mix of beliefs (a militant history also accompanied

Nichiren’s proselytizing), turned me off to the Nichiren Shoshu

religion. When I dropped out of the group, I was left with one

disappointment--my relationship with Jean ended, but I stayed in

her yoga class even though it felt a bit awkward until the last class. Jean

was the best yoga instructor I ever had. Something else felt a bit awkward, too.

At work, doing japa, my nam myoho renge kyo mantra made me uncomfortable, so

I decided to switch to the Tibetan mantra of compassion, om mani padme hum, but

after chanting nam myoho renge kyo for ten years, it was difficult to stay focused on

the new mantra. “What the hell,” I thought, “mantras are only tools anyway. Why should

sound syllables matter? The measure of success is keeping the mind focused.” So,

for me, it was back to chanting (thinking) nam myoho renge kyo over and over

and over again and again and again and again!

Immersed in all this fuss over “Who’s Right,” I was ready to move on!

When a new semester at school rolled around, I enrolled in a

Hindu religion class. I was familiar with some of the concepts

already, but I wanted to check out how the new professor taught the

course. My old professor, Professor Folkart, was on sabbatical in

India doing post doctorate work on the Jain religion, so there was a new guy

teaching his Asian religion courses. (Sadly, my professor never

returned to CMU. While riding a motorcycle in India he was killed by a

hit and run truck driver.)

Dishonest Buddhist

Mt. Fuji

Age of Dharma Decline

Summer, ’80

Jean was upset because having not studied under a practicing

Buddhist before I took my vows, I was, according to her, a dishonest Nichiren

Shoshu Buddhist. As a “card-carrying member of the group,” she thought I

should know more than I did. I agreed, and when she volunteered to

teach me, I was more than happy to oblige. Every other week, our

worship group met in a house in Midland (a twenty mile drive), and sitting

before the shrine of Gohonzon, a Japanese lady would lead us in the practice of

Gong Ho, a 15-minute recitation of Japanese script. Everybody chanted

along to the best of their ability. This practice began and ended the

worship session. Not knowing the language, I sat quietly while the

rest, (usually five or six participants) recited Gong Ho. To make a

long story short, I only attended two sessions with Jean and then

politely told her that I didn’t want to continue. I told her I needed

more time to read about the Buddhist sect before I continued my Gong

Ho practice. She was disappointed, but understood, and, as it turned

out, I was disappointed too, but not with Jean, nor even with

chanting, I was disappointed in the literature I found on the Buddhist

sect. I was not impressed.

The main problem with Nichiren Shoshu, for me at least, was that (I’m

actually embarrassed to say this) the followers believed that their

Buddhism was the last word on Buddhism, and by extension, the last

word on all religion. In Japan, around 1262, the monk Nichiren came

to believe that his mission in life was to alert his fellow Japanese

to abandon all other beliefs and religious practices. The last word in

Buddhism, for Nichiren, was to accept the teachings of the Lotus Sutra.

The Lotus Sutra, according to the monk, contained the highest truth of all the

Buddhist teachings, and was the only teaching that could be effective in during

the third and last age of Buddhism or Mappo, -- the Age of Dharma Decline.

Age of Dharma Decline

Summer, ’80

Jean was upset because having not studied under a practicing

Buddhist before I took my vows, I was, according to her, a dishonest Nichiren

Shoshu Buddhist. As a “card-carrying member of the group,” she thought I

should know more than I did. I agreed, and when she volunteered to

teach me, I was more than happy to oblige. Every other week, our

worship group met in a house in Midland (a twenty mile drive), and sitting

before the shrine of Gohonzon, a Japanese lady would lead us in the practice of

Gong Ho, a 15-minute recitation of Japanese script. Everybody chanted

along to the best of their ability. This practice began and ended the

worship session. Not knowing the language, I sat quietly while the

rest, (usually five or six participants) recited Gong Ho. To make a

long story short, I only attended two sessions with Jean and then

politely told her that I didn’t want to continue. I told her I needed

more time to read about the Buddhist sect before I continued my Gong

Ho practice. She was disappointed, but understood, and, as it turned

out, I was disappointed too, but not with Jean, nor even with

chanting, I was disappointed in the literature I found on the Buddhist

sect. I was not impressed.

The main problem with Nichiren Shoshu, for me at least, was that (I’m

actually embarrassed to say this) the followers believed that their

Buddhism was the last word on Buddhism, and by extension, the last

word on all religion. In Japan, around 1262, the monk Nichiren came

to believe that his mission in life was to alert his fellow Japanese

to abandon all other beliefs and religious practices. The last word in

Buddhism, for Nichiren, was to accept the teachings of the Lotus Sutra.

The Lotus Sutra, according to the monk, contained the highest truth of all the

Buddhist teachings, and was the only teaching that could be effective in during

the third and last age of Buddhism or Mappo, -- the Age of Dharma Decline.

Becoming Reacquainted With Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism

Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism

Summer 1980

It was lonely at first. Carin was living in Scotland’s Findhorn commune.

Her parents were excited over the idea. (Actually, I think they were just happy

to scurry their daughter away form me, a nice guy, but not really good

son-in-law material.) At work, I went from midnights to second shift.

My new shift, 4:30 p.m. to 1:00 a.m., helped me deal with Cairn’s

absence. The heavy going at the end of a love affair, those late night

pain hours, became less severe because of work. In fact, I used work time to

practice japa-- mind discipline. For six hours, I would do mental

work. The other two on the job hours, I would read or eat. Since my

work did not require a lot of mental attention, I had lots of

free time to silently repeat the mantra that was given to me eleven

years ago by the Nichiren Shoshu Buddhist group in San Diego. Now I

was really putting my mantra “nam myoho renge kyo” to use.

At that time, I was also taking a yoga class. It met on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

Jean, a graduate student in Art, taught the class and she was a very good

instructor. As it turned out, she was also practicing Nichiren Shoshu

Buddhism. After I told her about my early experience with the Buddhist sect

she said, “It’s not done like that anymore. You were street shockabukued;”

meaning that I became a Buddhist initiate before I had the foggiest notion of what

I was agreeing to. I defended myself by telling her that I had studied Buddhism in

an Asian Philosophy class before I became initiated and, therefore, I wasn’t forced

into doing something that I didn’t want to do. She didn’t agree with me and I had to

admit that I had no idea what made Nichiren Buddhism different from the

Buddhism I had studied in class. As it turned out, there was quite a bit of difference.

Shockabuku http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAlS_0wNUQg

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Our Beliefs About Realty Are Approximations

Animals were once, for all of us, teachers.

They instructed us in ways of being and perceiving

that extended our imaginations.

We watched them make their way through the intricacies

of their lives with wonder and with awe.

Petrified Wood from Yellowstone hike

Psychology Paper concluded

Experience is constrained; it cannot be separated from intentions.

When I notice my experience, I constitute my experience as an object

in order to notice it. Thus, that intentionality, by necessity, has to

be one of the underlying facets of my experience.

Experience is further constrained by the language I use to identify

and describe it. Language gives to the world a kind of stability that

may, or may not be there. Sense experience, for example, possesses a

kind of indescribability. For instance, the language I use to describe

the removal of a hot cherry pie from the oven will never capture the

whole experience. The smell of a freshly baked cherry pie cannot be

made linguistically clear, yet the language of the experience becomes

primary, thus making the experience itself secondary. At bottom, my

experience is never free from the methods I use to intentionally

constitute it. I would be living in a very different world if it were

otherwise.

Consider for a moment, the idea of temporal span or duration. The

continuity and stability of the world--and ego awareness--depends on this

temporal span, but, my experience is actually discontinuous! Each

conscious moment fades out of existence, while the next emerges only

to fade again and again. What is most notable, but never emphasized,

is the gap between these moments. I do not experience this gap; in fact, I

rarely notice the emptiness that co-exists duration, still, my experience is

made to flow even though it is full of holes and discontinuities.

Thus, I integrate my world and myself in time, but I also integrate my world

in space and, in that space, I find my I-space, which, in turn, is usually

located above the plane of my eyes and assumes responsibility for the

thoughts and images that arise in that space. The experience of a mental

"reaching," "grasping," or "making into something," triggers my

"experiencing I" and, by necessity, both the world and my experience of it

occurs in the clarifying structure of this spatiality. However, I-awareness or

knowingness, need not be bounded by an "I" or a physical body! The TSK

vision challenges our normal habits of perception; it challenges also the

belief of anthropologists that the body is a "thing" somehow inhabited

for the purpose of locomotion. It holds that the true nature of

humanity extends far beyond the limitations we bring to experience.

Recognizing that the world is the play of Space, Time, and Knowledge

speaks to the heart of Being and opens both the world and

consciousness up to a radically different set of alternatives. Any

thought or sequence of thoughts is bound to its origin, both in terms

of its history and intentionality, but that is not the true origin of

thoughts. Our space, time and knowledge is a product of a much more

encompassing and deepening Space, Time, and Knowledge. The true origin

of our thoughts is found there, in the "all encompassing" order. In

fact, according to Tarthang Tulku, if only we could get back to that

"virgin quality" of experience we could become truly free. He says:

"Throughout history, human beings have understood space as being

empty like the sky, and time as the irreversible flow of our lives and

of the seasons. There is an increasing emphasis on the knowledge

appropriate to this space and time—technical and factual knowledge;

the kind you find in an encyclopedia. Holding to this way of knowing

however, limits our ability to enjoy and appreciate life…. (But) Once

we understand Great Knowledge we do not need to change anything. We

recognize that we are part of a vigorous reality that shines through

all petty attitudes and preconceptions. Our `knowing' is fresh, sharp,

and spontaneous. It never needs to reduce the virgin quality of

experience to something that is `known' and therefore unworthy of

closer attention and appreciation."

In the TSK perspective--a vision not bound by a subject-object

relation-- time is not perceived as the stabilizing condition of the

world. And further, in that vision, experience is not always "of

something." The focus is rather on the emptiness at the heart of

experience--on the pervasive experience of an empty awareness. The TSK

experience—what could be called the ground or source of all specific

awareness’s—emerges out of and returns to that open, empty

awareness-space. The petty concerns of our daily lives prevent our

participation in the great feeling that is Time-Space-Knowledge, a

feeling within which we find space and meaning, time and change, and

knowledge and clarity.

They instructed us in ways of being and perceiving

that extended our imaginations.

We watched them make their way through the intricacies

of their lives with wonder and with awe.

Petrified Wood from Yellowstone hike

Psychology Paper concluded

Experience is constrained; it cannot be separated from intentions.

When I notice my experience, I constitute my experience as an object

in order to notice it. Thus, that intentionality, by necessity, has to

be one of the underlying facets of my experience.

Experience is further constrained by the language I use to identify

and describe it. Language gives to the world a kind of stability that

may, or may not be there. Sense experience, for example, possesses a

kind of indescribability. For instance, the language I use to describe

the removal of a hot cherry pie from the oven will never capture the

whole experience. The smell of a freshly baked cherry pie cannot be

made linguistically clear, yet the language of the experience becomes

primary, thus making the experience itself secondary. At bottom, my

experience is never free from the methods I use to intentionally

constitute it. I would be living in a very different world if it were

otherwise.

Consider for a moment, the idea of temporal span or duration. The

continuity and stability of the world--and ego awareness--depends on this

temporal span, but, my experience is actually discontinuous! Each

conscious moment fades out of existence, while the next emerges only

to fade again and again. What is most notable, but never emphasized,

is the gap between these moments. I do not experience this gap; in fact, I

rarely notice the emptiness that co-exists duration, still, my experience is

made to flow even though it is full of holes and discontinuities.

Thus, I integrate my world and myself in time, but I also integrate my world

in space and, in that space, I find my I-space, which, in turn, is usually

located above the plane of my eyes and assumes responsibility for the

thoughts and images that arise in that space. The experience of a mental

"reaching," "grasping," or "making into something," triggers my

"experiencing I" and, by necessity, both the world and my experience of it

occurs in the clarifying structure of this spatiality. However, I-awareness or

knowingness, need not be bounded by an "I" or a physical body! The TSK

vision challenges our normal habits of perception; it challenges also the

belief of anthropologists that the body is a "thing" somehow inhabited

for the purpose of locomotion. It holds that the true nature of

humanity extends far beyond the limitations we bring to experience.

Recognizing that the world is the play of Space, Time, and Knowledge

speaks to the heart of Being and opens both the world and

consciousness up to a radically different set of alternatives. Any

thought or sequence of thoughts is bound to its origin, both in terms

of its history and intentionality, but that is not the true origin of

thoughts. Our space, time and knowledge is a product of a much more

encompassing and deepening Space, Time, and Knowledge. The true origin

of our thoughts is found there, in the "all encompassing" order. In

fact, according to Tarthang Tulku, if only we could get back to that

"virgin quality" of experience we could become truly free. He says:

"Throughout history, human beings have understood space as being

empty like the sky, and time as the irreversible flow of our lives and

of the seasons. There is an increasing emphasis on the knowledge

appropriate to this space and time—technical and factual knowledge;

the kind you find in an encyclopedia. Holding to this way of knowing

however, limits our ability to enjoy and appreciate life…. (But) Once

we understand Great Knowledge we do not need to change anything. We

recognize that we are part of a vigorous reality that shines through

all petty attitudes and preconceptions. Our `knowing' is fresh, sharp,

and spontaneous. It never needs to reduce the virgin quality of

experience to something that is `known' and therefore unworthy of

closer attention and appreciation."

In the TSK perspective--a vision not bound by a subject-object

relation-- time is not perceived as the stabilizing condition of the

world. And further, in that vision, experience is not always "of

something." The focus is rather on the emptiness at the heart of

experience--on the pervasive experience of an empty awareness. The TSK

experience—what could be called the ground or source of all specific

awareness’s—emerges out of and returns to that open, empty

awareness-space. The petty concerns of our daily lives prevent our

participation in the great feeling that is Time-Space-Knowledge, a

feeling within which we find space and meaning, time and change, and

knowledge and clarity.

Questioning The Constraining Aspect Of Experience

Deep silence of the candle as an abyss of desire

Like rivers stream forward and then back again

To feel the favor of death – it is godlike feeling

Psychology 735 Paper

Our beliefs about realty are not `wrong,' they're simply

approximations of the way things are. Everybody, at one time or

another has had an altered space-time experience. That experience can

expand into experience of a higher order—experience that is not

dissociated or fragmented. In that "place" is found the liberation

that accompanies freedom from a persisting, independent, isolated

self. In that "place" there is nothing to get, nothing to discard, and

no place else we need to go. Tarthang Tulku says it this way:

"Through our bodies we can embody the full and infinite perfection of

Being: we can participate intimately in the interpenetration of all

reality, Being alive is like being invited to enjoy ourselves in a

beautiful garden where every sight and sound blends in perfect,

inexpressible harmony. Through our embodiment we can embrace this

precious opportunity, and merge with the perfect equilibrium of time,

space and knowledge."

After taking the Time-Space-Knowledge class, the "act of dissolving

into an opening" stopped sounding so strange. Opening to the

possibility of experience without carrying along "excess baggage" was

what the class taught us. Getting back to "raw experience" may sound

easy, but that was only to the uninitiated. In fact, the discovery of

"raw experience" had to be measured in incremental levels. In class we

talked about the phenomenological investigations that had revealed the

clinging baggage that, for the most part, remained invisible.

Like rivers stream forward and then back again

To feel the favor of death – it is godlike feeling

Psychology 735 Paper

Our beliefs about realty are not `wrong,' they're simply

approximations of the way things are. Everybody, at one time or

another has had an altered space-time experience. That experience can

expand into experience of a higher order—experience that is not

dissociated or fragmented. In that "place" is found the liberation

that accompanies freedom from a persisting, independent, isolated

self. In that "place" there is nothing to get, nothing to discard, and

no place else we need to go. Tarthang Tulku says it this way:

"Through our bodies we can embody the full and infinite perfection of

Being: we can participate intimately in the interpenetration of all

reality, Being alive is like being invited to enjoy ourselves in a

beautiful garden where every sight and sound blends in perfect,

inexpressible harmony. Through our embodiment we can embrace this

precious opportunity, and merge with the perfect equilibrium of time,

space and knowledge."

After taking the Time-Space-Knowledge class, the "act of dissolving

into an opening" stopped sounding so strange. Opening to the

possibility of experience without carrying along "excess baggage" was

what the class taught us. Getting back to "raw experience" may sound

easy, but that was only to the uninitiated. In fact, the discovery of

"raw experience" had to be measured in incremental levels. In class we

talked about the phenomenological investigations that had revealed the

clinging baggage that, for the most part, remained invisible.

Dissolving Into The Opening Of What Is

Psychology 735

Summer ‘79

Kum Nye

In Kum Nye practice there were three stages of unfoldment. In the

first stage an increased familiarity with body, thoughts, feeling, and

emotions occurred. Observing the levels of mind and the mechanism of

our ordinary consciousness was more the focus of the second stage, and

the last stage involved the actual transformation of negative energy

into positive energy. Because this was only an introductory class

there wasn't enough time to develop the stages. It was enough to find

out that they could be developed. I especially paid close attention to

the exercises at the second stage because they dealt with observing

the mechanism behind our ordinary consciousness, and that had always

been what interested me the most.

According to the TSK vision, our nature had an immense depth to it and

we could open to that depth. That vision challenged what, typically,

got understood as time, space, and knowledge. Opening a person up to

time, space, and knowledge, as opposed to what customarily got

experienced—the constraining aspects in one's time, space, and

knowledge—-- was what the practice of TSK was all about. Unlike most

paradigms, which defined reality, the TSK vision was about revealing

different aspects of reality by generously giving of itself without

ever altering or losing its own nature. In the end, it dissolved

itself in the opening up to what is, or at least that's what Dr. Beere

told us was supposed to happen. The exercises were all about getting

in touch with that new level of awareness.

Opening To Time, Space, And Knowledge

Ancient song

Call me home

Let me flow without time

Let me see in the light

Let me sound in the deep

Let me soar in the Silence

…of the Ancient Voice

Psychology 735

Summer `79

My how time gets away; I let the summer of ’79, the summer

before Carin and I took our Yellowstone trip, slip by without

a mention. Well, not to worry; these next four posts will catch me

and everybody else up. Actually, it was a productive summer!

It began with a workshop. The Psychology Professor, Don Beere, had

brought Larry Simmons to CMU to do the workshop on Time, Space, and

Knowledge (TSK). The lama, Tarthang Tulku, Rinpoche, had trained Larry

to spread his vision. The lama, from Eastern Tibet, was well educated

in all traditions of Tibetan Buddhism and authored the book, Time,

Space, And Knowledge, which expressed a new way of understanding the

nature of reality. In 1973, the lama established the Nyingma Institute

in Berkeley, California, the purpose of which was to provide a place

for the interaction of ancient wisdom with modern ideas. The Institute

offered an environment for meditation, self-growth, and intellectual

development. The primary person responsible for teaching and

presenting the TSK vision was Larry Simmons and he was also the person

who taught others how to give the workshops. For me, the workshop was

interesting and fun, but it was also just too much information

presented too quickly.

Not long after I attended the workshop, Professor Beere offered a

university class in Time, Space, And Knowledge. We (I was allowed to

sit in on the class) were taught how to release physical and mental

stress as part of the overall program that involved students in both

mental and physical levels of study. According to Tarthang Tulku, the

physical body was not a `fixed object' it was essentially flowing and

open. Using the books Time, Space, And Knowledge and Kum Nye, we

learned techniques for participating in the ongoing process of

`embodiment' of energies, which, according to Tarthang Tulku, made for

healthy bodies and clear minds. Those exercises included breathing

techniques, slow movements, self-massage, chanting, self-image,

concentration, and group process work—all of which were supposed to

put a person in touch with his or her own creative potential, as body,

mind, and emotions engaged the TSK vision. When one's energies were

made to flow more freely, clarity of vision was supposed to result,

and, for the most part that was exactly what happened.

Call me home

Let me flow without time

Let me see in the light

Let me sound in the deep

Let me soar in the Silence

…of the Ancient Voice

Psychology 735

Summer `79

My how time gets away; I let the summer of ’79, the summer

before Carin and I took our Yellowstone trip, slip by without

a mention. Well, not to worry; these next four posts will catch me

and everybody else up. Actually, it was a productive summer!

It began with a workshop. The Psychology Professor, Don Beere, had

brought Larry Simmons to CMU to do the workshop on Time, Space, and

Knowledge (TSK). The lama, Tarthang Tulku, Rinpoche, had trained Larry

to spread his vision. The lama, from Eastern Tibet, was well educated

in all traditions of Tibetan Buddhism and authored the book, Time,

Space, And Knowledge, which expressed a new way of understanding the

nature of reality. In 1973, the lama established the Nyingma Institute

in Berkeley, California, the purpose of which was to provide a place

for the interaction of ancient wisdom with modern ideas. The Institute

offered an environment for meditation, self-growth, and intellectual

development. The primary person responsible for teaching and

presenting the TSK vision was Larry Simmons and he was also the person

who taught others how to give the workshops. For me, the workshop was

interesting and fun, but it was also just too much information

presented too quickly.

Not long after I attended the workshop, Professor Beere offered a

university class in Time, Space, And Knowledge. We (I was allowed to

sit in on the class) were taught how to release physical and mental

stress as part of the overall program that involved students in both

mental and physical levels of study. According to Tarthang Tulku, the

physical body was not a `fixed object' it was essentially flowing and

open. Using the books Time, Space, And Knowledge and Kum Nye, we

learned techniques for participating in the ongoing process of

`embodiment' of energies, which, according to Tarthang Tulku, made for

healthy bodies and clear minds. Those exercises included breathing

techniques, slow movements, self-massage, chanting, self-image,

concentration, and group process work—all of which were supposed to

put a person in touch with his or her own creative potential, as body,

mind, and emotions engaged the TSK vision. When one's energies were

made to flow more freely, clarity of vision was supposed to result,

and, for the most part that was exactly what happened.

Saturday, October 22, 2011

To The Good, Better, Divine In All Of Us --SALUTE

Whispers of the north

Soon I will go forth

To that wild and barren land

Where nature takes its course

Whispers of the wind

Soon I will be there again

Bound with a wild and restless drive

That pulls me from within

And we can ride away

We can glide all day

Alone In My Apartment

So Long Old Friend

Winter of ‘79

A long time ago, I attended a lecture in Warner Auditorium. The

keynote speaker was an authority on value theory. I had hoped to learn

something from him, but I didn't. After the talk, as was my custom, I

went up to where the speaker took post lecture questions from the

audience. A Professor of mine, who himself had some original ideas on value

theory, was in the crowd. When he noticed me, he immediately came over

and started apologizing to me. He was apologizing for something he

felt uncomfortable about, something that he said to me the last time

we were together.

On that last time, I was taking his class, and, as was his style, he had

just posed a question to the class. I was not satisfied with the

class discussion of that question, so, after class, I went up to

him and asked, "What is the arête of man?" I was simply repeating

back to him the question he had asked the class to respond to. He

wouldn't (or couldn't) answer my question. (Arête is a Greek word

relating to purpose: the arête of a bow is to shoot straight.)

Do to circumstances beyond my control, I never returned to the Professor’s

class (I quite school and moved to Arizona) and because of my absence from

his class, my Professor had jumped to the conclusion that his teaching

method—his silence back when I asked him to respond to his own question,

had caused me to drop out of his class. He was wrong!

Now, upon my return to CMU, and standing in the crowd surrounding the guest

speaker on value theory, Dr. Gill wanted me to know that his silence to my question

was not surrender to the question concerning "man's lack of arête." Dr. Gill said,

“My silence back then was to make the point that the only person who can answer

that question is you!" What Dr. Gill was saying is that “a person's arête was always

peculiar to one's unique situation at the time of posing the question.” Dr. Gill was

apologizing to me because he had not answered my question; that is, until that very

moment, and at that moment, he completely won me over. I knew myself to be

standing in the presence of a man of impeccable character and generosity.

I continued to sit in on Dr. Gill’s classes until he died of cancer on Oct. 23, 1979.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Life Is Sweet, Goodbyes Are Tough

Lead, South Dakota

Oct. 25, 1979

After a breakfast of campfire eggs and bacon, Carin and I headed back

to Michigan. By late afternoon we pulled into the campground at the

foot of the Big Horn Mountains. It was located at the entrance to

Tensleep Canyon, the same canyon where I had an "out of body experience"

on a previous bicycle trip.

The next day, after a long day's drive, we pulled into Lead, South Dakota.

While there, I renewed my acquaintance with—the Barrios Family.

Sitting in Javier's living room brought back lots of memories, maybe a few too

many. However, drinking beer with Vicky and Javier, while listening to Leon

Russell sing Hank William's Good Night Irene on the stereo, made it

all worthwhile. I knew I was about to say goodbye to Carin (maybe

forever), but I also knew that I had said goodbye to Carole Sue from

on top of these same Black Hills--many times over. Life had a way of

repeating itself, whether you wanted it to or not, but sitting with old

friends while listening to great music got you through it! Drinking

my beer, I knew full well that when Leon was through singing, it would

be the Grateful Dead's turn. Javier would see to that!

Nov. 1979

Carin's parents just left my place and took their daughter with them.

The emotional good-byes were short and sweet. In the next few days she

will board a plane enroot to Finhorn, a colony of people tending a

"magic garden" somewhere in Scotland. Carin and I never made promises

to each other. We lived together for almost a year and

half. We loved and respected one another. Many times in the past we joked about

getting married. I think it was back in July that I tried to get

serious about it, but her response was a silent, icy stare. I dropped

the idea after that.

She was 22, a free spirit, and ready for independence. I had just

turned 31 and was four years into the not so sensational work of

self-development. Carin graduated "summa cum laud" while I, after

twelve years, had just received my degree. Her life was just getting

started, while mine meant little more than a scratch on the wall of

another day. Our "getting together" would have, most likely, violated

some kind of natural law. I guess that's why we chose not to talk

about it. I knew there would be no Carole Sue type break down or

collapse for me. If I had learned anything from my experience with

C.S., it was how not to let something like that happen again.

Just before Carin and I went on our vacation, I was sitting in on yet

another class taught by Professor Gill. In the past, I had sat in on

full semester classes taught by Dr. Gill in-- The Philosophy Of

Literature, Myth, and Spinoza. I had also spent truncated time in the

classes he taught concerning Value Theory, Plato, Zen and Symbolic

Logic, and Freedom. In all but the last couple classes, I challenged

him at every opportunity. I needed to know what he knew. What I

finally concluded was that John Gill was not an instrument conveying

knowledge, but rather, as a teacher exuding great sensitivity, i.e., he was

a deeply emotional, educational, experience. After I got back from my

vacation with Carin, I found another Professor teaching his Freedom

class. John Gill died of cancer on October 23, 1979. He was 69 years old.

Mt. Teewinot Magic Comes Through Again

Teton National Park

Sept. '79

After Madison, we drove down to the Teton Mountains, just south of the south

Yellowstone entrance. The weather remained good, but at Colter Bay

Campground it was a little crowded for my taste anyway. The next day we drove

down to the Jenny Lake. The first time I had camped at Jenny Lake I

climbed Mt. Teewinot and lost my wallet, but found it the next day.

The second time I camped there, it was late fall, and I almost got

frostbite on my ass. I met this sex-starved nurse from Seattle, but

of course, I didn't tell Carin that. This time around, the weather was

beautiful, and I was enjoying it with the woman I loved. This was

going to be our last stop before we headed home. We planned to make it

a rest stop. But the Tetons had a way of reinvigorating even the weak

and lame. After resting a day, Carin suggested we climb Mt. Teewinot.

I didn't try to change her mind (I knew the mountain would do that for

me), but I did suggest that we check out a few of the sights before

the big hike. She agreed, so we hiked up to Hidden Falls and

Inspiration Point—absolutely beautiful scenery. On the third day we

headed out to Mt. Teewinot and managed to climb up to a waterfall.

From that height, we had an excellent view of the surrounding

countryside. Carin agreed that we had climbed high enough. The best part

of the whole trip turned out to be spending that day on the mountain, just the two of us.

What a memorable, beautiful, hot sunny day, that was!

Back at the campground, we had an early dinner and then went for a

drive hoping to see some wildlife. Perhaps it was the dryness, or

perhaps we were unlucky, but we didn't see any animals. In fact, on

this trip the sum total of all the wildlife we saw was: three cow

moose, one calf, a coyote and a buffalo. In the backcountry we did

hear the sounds of some distant bugling elk, but unfortunately we

didn't get to see any.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)