Thursday, December 29, 2011

Jean Paul Sartre

Innate Structuring Capacity—Reciprocal Movement

Jan. ’12

Reciprocal Movement, –The Carrier Of Free Thought, The Same Free Thought That Brings Into Being Language, Myth, Science, Ethics, And Civilization

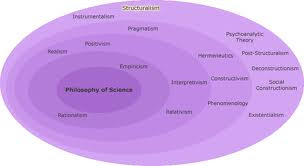

Identifying Sartre’s philosophy as structuralism is, I am aware, pushing the envelope. However, an authority on structuralism has proposed this option (without, I might add, elaborating on it.) “One might go as far as to say…that structuralism is analogous to Sartre’s view of consciousness — it is what it is not, and it is not what it is.” [Jean-Marie Benoist, A Structural Revolution, 1975, p. 1] In Sartre’s book Being And Nothingness, his chapter on Being-For-Itself is subtitled “Immediate Structures of the For-Itself.” [Jean-Paul Sartre, Being And Nothingness, 1966, p. 119] Structure is not hidden in Sartre; it’s just that on the whole Sartre’s book is a polemic against reading structure as anything more than appearance.

In the representation of Sartre’s thought as “consciousness is what it is not, and it is not what it is,” we find reciprocal movement, the same reciprocal movement encountered, in one form or another, in all the structuralists I have discussed hitherto in this paper. Specifically, Sartre defines the consciousness of the transcending For-itself (our self-space) as: “Consciousness is a being such that in its being, its being is in question in so far as this being implies a being other than itself.” [Ibid. p. 801] In an extrapolation from Sartre’s definition of the consciousness, Benoist describes that relationship as: “it is what it is not, and it is not what it is,” while I describe it as: being-what-is-not-while-not-being-what-is. In both cases, however, we end up with a definition for reciprocal movement.

This double movement is represented on many levels in Sartre’s exegesis on being and nothingness. This double movement becomes very specific in Sartre’s description of his pre-reflective Cogito. In so far as we find ”nothingness” at the center of Cogito, consciousness per se must be understood to be set apart from itself, therefore, Sartre’s pre-reflective Cogito will always form one pole of our conscious experience while the “objects” of consciousness will take their place at the other pole of conscious experience. In this way, Sartre is able to dispense with Descartes’ Cogito on the grounds that consciousness cannot be separated from its object. This condition, where the pre-reflective Cogito becomes a preexistent condition for the conscious awareness of objects, establishes the double movement of conscious reflection — the object of consciousness less the pre-reflective Cogito, and the pre-reflective Cogito less the object of consciousness. Depending on where “you” focus your concern, the content of consciousness is either pushed to the front of consciousness (the unreflective consciousness), or, the object of consciousness is pushed into the background, as the “negation of consciousness” is brought into the foreground (the reflected upon object of consciousness).

Together, our pre-reflective Cogito and the object of consciousness form our conscious experience of the knower-known dyad (this is also the origin of “time of mind,” the same experience that so perplexed St. Augustine that he mused, -- “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.)In so far as this double movement turns on the pivot point of pure negation, the known exists for the knower, but the knower can never be fully known. As self-consciousness rises in consciousness, it is denied the possibility of becoming fully self-aware. This result, the incompleteness of self, brings us back to Sartre’s original definition of consciousness, or, “consciousness is such that in its being its being is in question in so far as this being implies a being other than itself.” This movement, the symbol-generating movement of free thought, the movement that makes thinking possible, emancipates language, myth, science, and morality. In the absence of this movement, thinking (or thought) is restricted to the manipulation of signs—mere sensual indicators, minus the symbols that carry the significance of those same indicators.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment